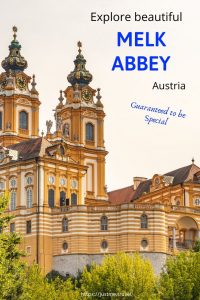

There are not enough adjectives to describe Melk Abbey. My first sighting of Melk Abbey, a Benedictine monastery, took my breath away and it took a while before I could pick my jaw up off the ground. This beautiful, beautiful monastery (duplication not a typo) in Lower Austria should be on everyone’s European itinerary.

Melk Abbey is a masterpiece of Baroque architecture. It is Austria’s largest Baroque structure. Perched high on a cliff overlooking the old town of Melk and the Danube and Melk rivers, it sits within the Wachau Valley, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The abbey you see today was built between 1702 and 1736. But Melk Abbey is 900 years of history – all evidently told in the abbey’s museum. Originally a palace, Melk Abbey was gifted to the Benedictine monks in 1089 and has remained an active abbey ever since. Today, Melk Abbey has 30 monks (ranging in age from 21 to 96 years); a co-educational secondary school with 900 pupils; and extremely well presented, minimalist museum; and a church that I can only describe as ostentatious.

From every angle, Melk Abbey is impressive. I lost count of the number of times I said, “Oh my goodness”. Swathed in ochre-coloured paint, Melk Abbey is just the most beautiful building to behold. You might have gathered by now that I fell in love with Melk Abbey. And the guided tour cemented my love.

The guided tour through Melk Abbey commenced with a meet and greet in the large outer courtyard, the Gatekeeper’s Courtyard. In this courtyard, you will find the oak wooden statue of Saint Coloman. The statue is 150 years old and the oak was sourced from the abbey’s forests. Saint Coloman was Austria’s first patron saint until 1663. He is still the patron saint of Melk Abbey and the town of Melk.

From the Gatekeeper’s Courtyard, it was through the Benedict Hall and into the Prelate’s Courtyard. In this latter courtyard were four vivid, contemporary frescos; replacing the Baroque frescos that were unable to be restored. These frescos represent the four cardinal virtues – Prudence, Temperance, Justice and Fortitude. The modernist style of the frescos caused some controversy as people tried to adjust to the move away from the original, and expected, Baroque style.

The fountain in the Prelate’s Courtyard is a copy of the Coloman fountain. The original, removed from Melk Abbey in 1722, now stands in Melk’s Town Hall Square.

Leaving the Prelate’s Courtyard through a narrow passageway, the Imperial Staircase leads up to the Imperial Wing.

The Imperial Wing was originally designed for the imperial court. Here, we find the Imperial Corridor and the imperial rooms (now housing Melk Abbey’s museum). A lot of ‘imperials’ happening here!

The Imperial Corridor, at 200 metres long, is impressive. The Corridor is hung with portraits of Austria’s rulers – from the first Babenberg Emperor, Leopold l, to the last Habsburg Emperor, Karl l. There are more portraits of Habsburgs because they ruled for longer.

The Melk Abbey museum, in the imperial rooms to the left of the Imperial Staircase, is extremely well set up and informative. It is minimalist in a positive way. That is, you get a good overview of the history (past and present) of the abbey, of its cultural, political and economic functions, but you are not left feeling overwhelmed; feeling as though there was too much to take in and, therefore, coming away none the wiser. No information overload here.

The museum comprises of 11 small rooms. The overriding theme of the museum is, “The Path from Yesterday to Today: Melk Abbey in its Past and Present”, with each room having its own individual theme. What follows are snippets of, in my opinion, interesting information taken from the guide’s explanations throughout the museum tour and my impressions.

Room 3 (“The Ups and Downs of History”) has a wavy floor, representing the ups and downs of life. The flooring is not the original Baroque because Napoleon was an unfortunate guest who burned documents on the floor.

Rooms 5 and 6 are a tribute to Melk Abbey’s contribution to the Baroque period. The Baroque period was a time in history of excess and all that glitters (gold, and more gold). “Heaven on Earth” seems to me an appropriate theme for this period. However, Room 7, with its, “In the Name of Reason” theme, represents new times and a sensible, frugal monarch. Joseph ll said the Baroque style was too expensive. But perhaps he was a little too frugal. Taking the Baroque style to the opposite extreme, he only allowed one coffin per church. The coffin designed to meet this requirement had a bottom that would open, allowing the corpse to drop through. Thus, the coffin could be used again.

Room 10 (“To Glorify God in Everything”) contains a 17th century iron chest used for secure storage and transporting the abbey’s most important documents and treasures. The chest has a convoluted locking mechanism, comprising of 14 locks that are still working.

The detailed model of Melk Abbey housed in Room 11 (“Motion is a sign of Life”) turns so you can see all sides unobstructed. There is a mirror on the ceiling to enable a view into the courtyards of the model.

The Marble Hall was a place to receive guests and dining hall for the imperial family. The name ‘Marble’ Hall is somewhat misleading as only the door frames are true marble. The ‘marble’ on the walls is faux marble. However, this is easily forgiven by the magnificent ceiling fresco that is complemented and framed by stunning architectural painting.

Magnificent views of the town of Melk, and the Danube and Melk rivers are to be had from the Terrace that connects the Marble Hall with the library. The Terrace also provides a great view of Melk Abbey church.

The library is the second most important room in any Benedictine monastery; second only to the church.

My favourite library to date has been Coimbra University library in Portugal. However, the competition between that library and Melk Abbey’s library would be a close contest. Both are stunningly beautiful. There is something uniquely special about the mix of dark wood and old books.

Melk Abbey library houses approximately 10,000 volumes, with manuscripts dating back to the 9th century. The uniformity of the books in the inlaid bookshelves is due to them all being bound to match. With internal balconies, wooden sculptures, a huge free-standing world globe, figurines and frescoed ceilings, the library is an entrancing vision. It also exudes peace and tranquillity; a place where I could easily spend hours just sitting and soaking in the atmosphere. I know I am waxing lyrical here, but I can’t help it. Melk Abbey library does that to me. No wonder Umberto Eco conducted his research on his book, The Name of the Rose in Melk Abbey’s library. But more on that later.

The upper floor of the library, reached by a spiral staircase, is not open to the public.

The guided tour ended in the library. I lingered to absorb the library’s ambiance before heading to the church on the recommendation of the guide.

My visit to Melk Abbey’s church, not part of the guided tour, was very brief as I am over what I can only describe as ostentatious, Baroque churches. Of note, however, is the Altar of St. Coloman. Here you will find a sarcophagus with, we are told, the remains of St. Coloman, the patron saint of Melk Abbey.

Photography was not permitted inside Melk Abbey’s museum, the Marble Hall, the library, or the church.

You don’t have to take the one-hour guided tour of Melk Abbey (except in the winter months). However, it is my opinion this would be false economy as the explanations provided by the guide throughout the tour were invaluable. The guide’s story telling brought Melk Abbey alive; revealing all its traits.

Melk Abbey’s literary connection is not just confined to the books in its historical library.

The Name of the Rose, written by Umberto Eco (1980), is a historical murder mystery (a medieval whodunit) set in an Italian Cistercian monastery in 1327.

But what does a story about murders in a Cistercian monastery in Italy have to do with a Benedictine monastery in Austria? The connection is Melk Abbey’s magnificent library. You see, the focal point in The Name of the Rose is the library where all the murders take place. Melk Abbey’s library is said to be Eco’s inspiration for the library in The Name of the Rose.

But the connection goes further than that. One of Eco’s main characters in The Name of the Rose is Adso of Melk, a Benedictine novice from Melk Abbey. The Name of the Rose is Adso of Melk’s story as he is the narrator. As way of introduction, Adso of Melk informs us he is writing his narrative, now an old man, at Melk Abbey. On the last page of The Name of the Rose, Adso of Melk tells the reader he is leaving his manuscript in the library of Melk Abbey.

In summary, make the effort to visit Melk Abbey. You won’t be disappointed. I guarantee it is something special.

If you like this post, PIN it for keeps

Disclaimer: This post contains no affiliate links. All views and opinions are my own and non-sponsored. All photos are my own and remain a copyright of Joanna Rath.